ARCHITECTURE | Mies van der Rohe in Toronto + Berlin :: The Most Beautiful Pavilions

In previous posts here and here about two libraries in Burnaby, British Columbia, I compared those structures with their antecedents in Mies van der Rohe’s pavilion architecture, singling out his Barcelona Pavilion (1929) and Crown Hall at ITT (1956) as exemplars of The International Style. In those posts, I called Mies “the master of the pavilion.”

Perhaps my favourite Mies pavilion is the astounding banking hall he created in Toronto for the Toronto-Dominion Bank, part of the Toronto-Dominion Centre.

The original TD Centre consisted of two skyscrapers plus the banking hall. The first phase to open was the TD Tower, which was symbolically dedicated on Canada’s 100th birthday, 1 July 1967.

Photo > “Material/Dematerial” by Steve Hoang, Flickr

At 56 stories and a height of 222.86 metres, the TD Tower is the tallest Mies structure in the world (Philip Johnson called the entire complex “the largest Mies in the world”).

°

°

°

Toronto in the ’60s: before and after the TD Centre

(with thanks to “Toronto Without the Tower” by Franny Wentzel)

°

°

°

When completed, the TD Tower was Canada’s tallest skyscraper, so naturally there was an observation deck on the top floor (which was closed to the public when the CN Tower made it redundant in 1976).

Photo > “Mies Curving Inward” by End User, Flickr

Photo > “Toronto’s CN Tower & TD Centre 1975” by CanadaGood, Flickr

I like the entire composition of buildings, but the single-storey, double-height banking pavilion at the corner of King and Bay Streets stands out amongst Mies’s architectonic composition. It opened for banking business in 1968.

A huge, column-free space, this banking pavilion commands our attention because of its proportions and detailing.

When I lived in Toronto, I would often pass though the pavilion just to see the Master’s work and gaze in amazement at its sheer size and luxe style. It was always a pleasure to plop myself in one of Mies’s regal Barcelona Chairs and just stare at that amazing waffle-grid clear span ceiling, seemingly defying gravity with no means of support other than the corresponding steel I-beam columns around the peripheral walls.

The Toronto-Dominion Centre is a beautiful space; one that put Toronto on the architectural map in the mid-sixties, forever changing the city’s skyline and, perhaps, the way its citizens viewed themselves.

It was Mies’s last major work before his death in 1969.

Photo > “TD Centre” by fortinbras, Flickr

Photo > “half reflected” by Sam Javanrouh, Flickr

Photo > “Toronto-Dominion Banking Pavilion” by Steve Hoang, Flickr, Flickr

Photo > “tdcc” by wyliepoon, Flickr

Photo > “tdcc” by wyliepoon, Flickr

Photo > Peter McCallum/ Detlef Mertins, Architecture Week

Photo > John Vetterli, Flickr

Photo > TD Bank Financial Group

In 2007, the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada declared the Toronto-Dominion Centre a masterpiece of the twentieth century. It stood in good company: all five winners were buildings that I love.

Habitat ’67, Montréal, QC | 1967 | by Moshe Safdie and David, Barott, Boulva Associates

Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, BC | 1965 | by Erickson/Massey

Smith House II, West Vancouver, BC | 1964 | by Erickson/Massey

Wolf House, Toronto, ON | 1974 | by Diamond & Myers (designed by Barton Myers)

Toronto-Dominion Centre, Toronto, ON |1967 (First phase); 1991 (Sixth phase) | by Bregman & Hamann Architects, John B. Parkin Associates, and Scott Associates with Design Consultant Mies van der Rohe

ROYAL ARCHITECTURAL INSTITUTE OF CANADA: Prix du XXe siècle 2007 Recipients — The Toronto Dominion Centre

A large cluster of buildings in downtown Toronto, consisting of six towers, covered in bronze-tinted glass and black painted steel. Three structures are arranged on a granite plinth, with the Banking Pavilion anchoring the site at the corner of King and Bay Streets.

The buildings are confined to a rigid structural grid set out across the plinth’s top, and each is offset to the one next to them by exactly one bay of the grid, allowing views to ‘slide’ open or closed as one moves through the site. On the north side, within the space created by the situation of the towers and pavilion, a large granite plaza provides a formal entry to the complex. Blurring the distinction between interior and exterior, the granite surface of the plaza extends through the glass lobbies of the towers and through the Banking Pavilion.

– RAIC

°

°

°

The history of the TD Centre is linked to the visionary Allen Lambert (1911-2002), former President and Chairman of the Board of the Toronto-Dominion Bank, and Phyllis Lambert, his sister-in-law. It was she that recommended Mies as “design consultant” for the project, after rejecting the “official” architects’ (John B. Parkins Associates) initial design proposal.

Phyllis Lambert is the doyenne of Canadian architecture and the éminence gris behind so many important buildings of the twentieth century, starting with Mies’s Seagram Building in New York (completed in 1958). That masterpiece of The International Style was designed as the headquarters for the Canadian distillers Joseph E. Seagram’s & Sons. Lambert, the daughter of Samuel Bronfman (Seagram’s CEO), convinced her father that Mies was the right architect for the headquarters. He consented but insisted that she serve as Director of Planning for the project. She’s a fascinating woman, deserving of a post or two of her own on designKULTUR.

Philip Johnson, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and Phyllis Lambert with a photograph of the Seagram Building maquette

Mies van der Rohe and Phyllis Lambert with a maquette of the Seagram Building

Maquette of the Seagram Building

The Seagram Building: the final product

°

°

°

The Toronto-Dominion Centre can best be viewed as a gigantic exercise in public relations for a company wishing to project a future-forward image after the 1955 merger of the Bank of Toronto and the Dominion Bank. It was architecture as an image-shaping device; the ultimate “rebrand.”

The identity of the new bank was established through an active public relations campaign focused on customer service — “The Best in Banking Service,” the Bank’s first slogan evolved into the highly successful “The Bank Where People Make the Difference.”

The competitive banking environment, and the need for effective integration of two administrations, led the Bank to re-assess and modernize business practices and methods through the second half of the 1950s. Procedures were streamlined, new technology was introduced, and the human resource function acquired new importance as the Bank placed increased weight on customer service and product knowledge.

The Bank’s emergence as a forward-looking institution was highlighted by the announcement in 1962 that it would have a new and very high profile head office in downtown Toronto. The Toronto-Dominion Centre, designed by Mies van der Rohe, the leading architect of the day, would include the tallest building in Canada. It would revolutionize both the skyline of Toronto and the public perception of TD.

– Wikipedia: Toronto-Dominion Bank

The essence of Mies’s genius lay in his exquisitely proportioned spaces, utmost attention to detail (his famous dictum was “God is in the details”), and the use of elegant materials where “Less is More.” These three points are crucial to any analysis of Miesian architecture.

Miesian attention to detail and quality: the typeface Mies designed for the Centre.

Photo > End User, Flickr

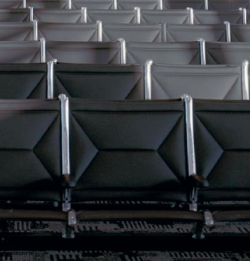

Miesian attention to detail and quality: rows of Flat Bar Brno Chairs, English oak, and travertine at the TD Centre

Photos > ocad123, Flickr

Miesian attention to detail and quality: Barcelona Table with fishbowl and yellow flowers.

Photo > “TD Boardroom Flowers” by bottlerocketprincess, Flickr

My second favourite pavilion by Mies is his New National Gallery in Berlin. It was Mies’s last building; the one he didn’t live to see through to its completion.

I’ve been to that city twice, and both times I’ve made a pilgrimage to see this important piece of twentieth-century architecture only to find the gallery closed. So, I will have to leave my complete review of the building until I go back to Berlin and try a third time.

Meanwhile, here are some beautiful stamps honouring Mies and his gallery, plus a couple of shots of the exterior that I took in 2008:

PHYLLIS LAMBERT on CHARLIE ROSE, 12 July 2001

An hour panel discussion about the talent and career of 20th century architect Mies van der Rohe with Barry Bergdoll, co-organizer of Mies in Berlin at the Museum of Modern Art, Phyllis Lambert, Director of the Canadian Center for Architecture, and Paul Goldberger, architecture critic for The New Yorker. They discuss the legacy of van der Rohe, who revolutionized the American city skyline with his signature steel and glass box international-style structures. They also talk about the two exhibitions of Mies’ work showing simultaneously at the Museum of Modern Art and the Whitney Museum in New York City.

UPDATE > Sorry, Charlie has taken Phyllis off his list of archived guests. Too bad, because it was a fascinating interview, one in which the interviewer and interviewee were truly equal. dK

°

°

°

THE PAVILION THAT STARTED IT ALL: BARCELONA, 1929

A rare photo of a smiling Ludwig

The Globe and Mail | Seagram heiress Phyllis Lambert: An architectural visionary looks back PDF

About this entry

You’re currently reading “ARCHITECTURE | Mies van der Rohe in Toronto + Berlin :: The Most Beautiful Pavilions,” an entry on designKULTUR

- Published:

- 2010/06/09 / 05:19

- Category:

- ADVERTISING, ARCHITECTS + ARCHITECTURE, CANADIAN DESIGN, CITIES | BERLIN, CITIES | TORONTO, CORPORATE IDENTITY, EXHIBITIONS, GRAPHIC ARTS, LOGOLANDIA, STAMPS + MONEY, TYPOGRAPHY, URBAN PLANNING

- Tags:

- "Architecture is the will of an epoch translated into space", 2014 Venice Biennale Golden Lion Recipient, 20th-century architecture, Allen Lambert, Arthur Erickson, “Less is more”, “the largest Mies in the world”, Barcelona Chair, Barcelona Table, Barton Myers, Brno Chair, Diamond & Myers, Erickson/Massey, God is in the details, Habitat 67, John B. Parkins Associates, Mies van der Rohe, MoMA Mies in Berlin, Moshe Safdie, Neue Nationalgalerie, New National Gallery Berlin, Philip Johnson, Phyllis Lambert, Prix du XXe siècle 2007, RAIC, Seagram Building, Simon Fraser University, Smith House II, Toronto architecture, Toronto-Dominion Bank, Toronto-Dominion Centre, Whitney Mies in America, Wolf House

2 Comments

Jump to comment form | comment rss [?] | trackback uri [?]